History of the Harris-Cameron Mansion in Harrisburg, PA

In the early 1700′s, Harrisburg’s founder John Harris Sr. immigrated to the area from Yorkshire, England after receiving a land grant. When he first arrived, Harris Sr. built a homestead on the bank of the Susquehanna River and established a trading post, and then a successful ferry business that would funnel much of the Scottish, irish, and German immigrants west for over fifty years. Known for his fair dealings and good relationship with local Native Americans, Harris Sr.’s also facilitated successful relationships between new settlers and the local Native American population.

After Harris Sr. died in 1748, John Harris Jr. inherited the homestead and business and continued the family legacy of good relationships with local Native Americans – during the French and Indian War two notable “council fires” were held at the Harris home for talks between the Indian Nations, local governing officials, and British representatives.

In 1766, after the French and Indian War ended, Harris Jr. decided it was time for a more substantial house for the family. Tired of evacuating their current homestead whenever the river flooded, Harris Jr. chose the current site of the mansion after observing that even during the worst flooding, the river had never reached the top of the rise in the ground the mansion sits on.

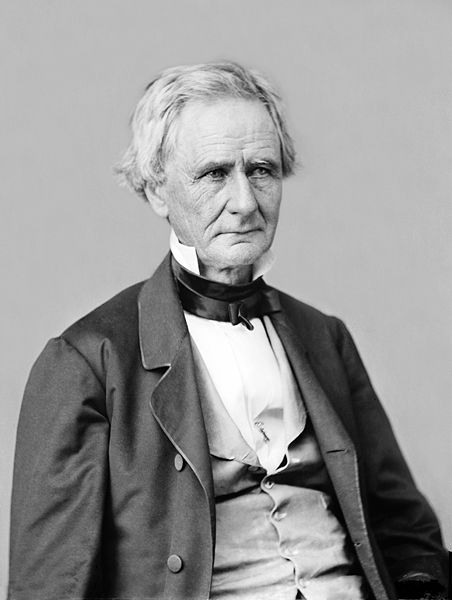

Originally constructed in the Georgian style of architecture using locally quarried limestone, the house had a total of eight owners over the years and each made changes to the house. In the early 1800′s a rear wing was added to the original mansion, and in 1863 the house underwent significant changes when Simon Cameron (seven-time U.S. Senator, President Lincoln’s first Secretary of War, and former Ambassador to Russia) purchased the house.

“Having made an offer of $8,000 for the Harris Mansion, Cameron left for Russia. He traveled throughout Europe and stopped in England, France, Italy, and the German states. While making his way to Russia, Cameron was shopping for furnishings for his new house. In the parlor are two 14-foot-tall (4.3 m) pier mirrors, as well as mirrors above the fireplaces that came from France. The fireplace mantles are hand-carved Italian marble, and the alcove window glass is from Bavaria.

Cameron disliked being politically isolated in Russia, so he returned to the United States and resigned the post in 1863. After finalizing the purchase of the house, Cameron set out to convert it to a grand Victorian mansion in the Italianate style. He hoped it would be suitably impressive to his business and political associates. Cameron added a solarium, walkway, butler’s pantry, and grand staircase. He also had the floor lowered three feet into the basement in the front section of the house, because the 11-foot ceilings in the parlor could not accommodate his new 14-foot mirrors.”

-Wikipedia entry on the Simon Cameron House

In the early 1900′s, Cameron’s grandson Richard Haldeman, the last of the Cameron family to live in the home, made more changes when he redecorated, modernized the mansion, and added the West Alcove to the house. When he died, his sister donated the house and other family items to the Historical Society of Dauphin County.

Historic Porch Restoration at the Harris-Cameron Mansion

In 2013, we were contracted to repair and restore the Victorian style porch. The porch was in disrepair – the brick piers that supported the floor were falling apart, the corner of the roof system was completely rotted out, there was a vermin infestation underneath the porch that was compromising the structural stability of the porch. In addition to the disrepair, there had been alterations to the style of the porch over the years and the Historical Society wanted the porch both repaired and returned to its original style.

The major contributing problem that needed to be addressed was that the spouting and gutters weren’t emptying water away from the porch because the porch had settled and moved. There had been attempts to repair the porch to keep it from settling, but they didn’t last or weren’t correct repairs – at one point someone had actually strapped the porch to the stone house wall to try and keep it from sliding by putting metal gussets at the spots where the framing was coming apart and separating at the corners. But no one had ever addressed the problems with the porch foundation which was causing the settling and moving.

For the project, we started with demolition – a very careful demolition. There were a lot of important materials on the porch that we encased in plywood boxes to protect them during the demolition process. The stone where George Washington stood in 1780… An original sandstone step that was already cracked… All the important elements of the porch were carefully protected to prevent any damage during the construction process.

After demolition, we addressed the foundation issues by pouring five concrete footers at each of the column locations since that is where the porch had been failing and where the roof was sagging. There had been brick piers there that we rebuilt with a combining of the existing brick and salvaged brick we purchased to match, but there had never been a frost-line footer under the porch.

All of the existing trim, arches, columns, floor, and skirtboard that could be salvaged were brought back to our shop where we removed the lead paint, repaired the pieces where necessary, fabricated new pieces as needed to match existing pieces, and reassembled them. We fabricated new columns and elliptical arches from mahogany wood to match the style of the existing columns and arches that were re-used. Several columns still had the original trim that we could copy when turning all of the capitals and column pieces.

We were able to level and save the porch roof by putting a large, carrier beam on the front of it. We also put all of the columns and capitals on metal pipes before we installed them so we could put the columns on without cutting them in half.

The flooring and ceiling also needed repaired and replaced at some spots. The original wood was vertical fir, but using fir would have been tremendously costly. Mahogany was chosen instead for its availability and its cost. While mahogany would not have been used as an exterior wood when the porch was originally built, it is an acceptable replacement material in preservation standards and actually holds up better as an exterior wood than many original woods.

This project was a collaborative effort between Richard Gribble at Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects, McCoy Brothers, and the Historical Society of Dauphin County, and us.